Hey #physed’ers! It’s been awhile since I posted anything about physical literacy (like, 2 years…). Oh well – sometimes formulating ideas, searching for evidence and getting cool graphics designed just takes time!

What follows is an introduction to a framework that I’ve been working on with Andrew Morgan (a stellar MEd graduate) over the past 5 years. I first wrote about physical literacy and began speaking on ‘Praxis’ in 2015. Since then, we’ve been working more on the framework, Andrew completed his thesis (yay!) and we published the initial paper in UNESCO’s Prospects Journal. Next to come is a paper on the pilot project that Andrew completed with 3 high school PE teachers to ‘test’ the framework. However, academic papers are only one avenue to get ideas out there. As part of our commitment to knowledge creation and dissemination, we wanted to share this work in a format (this blog!) that ALL can access.

We also thought we’d try a different form of peer-reviewed feedback – YOU!

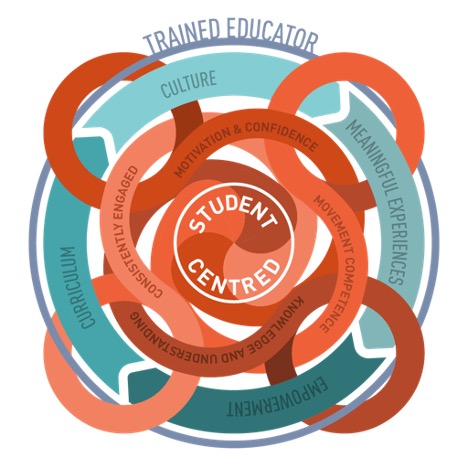

Andrew and I would really like to hear what you think of the framework, the evidence and how it might help with implementing physical literacy in your context (maybe it can work for sport, community and recreation too?). You can comment below or email me at dgleddie@ualberta.ca. Here’s the whole thing in one very fun diagram – an explanation of each part follows.

Physical Literacy Praxis

Copyright Douglas Gleddie & Andrew Morgan

For some of the background to the framework, check out the earlier conceptualization of physical literacy praxis. Let’s dive right into the structure and a brief look at the evidence behind it.

Trained Educator. This is the starting point for the framework. A trained educator is someone who values PE as part of whole child education. We specifically chose NOT to say PE specialist as the term above is more inclusive of those persons with continued professional development (CPD) in the area (Mandigo et al. 2004, Miller, 2017). These are teachers who: 1) value PE, 2) are knowledgeable, 3) are lifelong learners (CPD) and, 4) engage in pedagogical best practices.

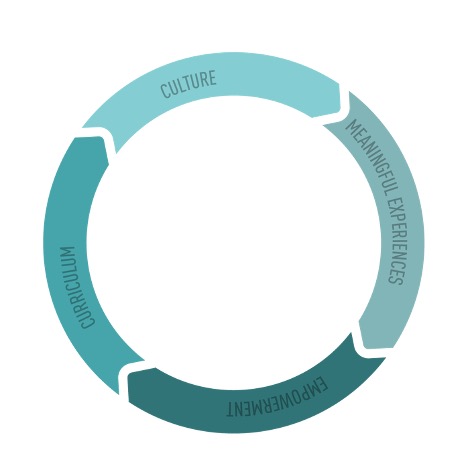

CULTURE Ensure a welcoming, caring, respectful and safe learning environment. Respect diversity, and nurture a sense of belonging and a positive sense of self for all students (Konishi et al, 2017). The teacher (trained, of course!) is autonomy-supportive, building solid relationships with students, and structuring the environment so that students are optimally motivated for physical education (Van den Berghe et al, 2014).

Meaningful Experiences Pulls from the idea of creating joy-based physical education (Kretchmar, 2008) as well as the emergent framework of Meaningful PE (Beni, Fletcher and NiChronin, 2017 – and others!). Features include: social interaction, challenge, fun, increased motor competence, personally relevant learning, and MORE… Meaningful PE is a rapidly evolving area with a lot of emergent research and a beginning shift toward implementation.

Empowerment Based in some of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility in PE (Hellison, 2003) research featuring a strong teacher–student relationship; empowering students; integrating responsibility into physical activity; and promoting transfer of responsibility (Pozo et al., 2016). A PE program that supports empowerment: 1) provides opportunities for student agency and ownership, 2) encourages the development of life skills, 3) the attainment of personal goals and, 4) engagement in disciplinary actions that maintain a caring relationship, (Gano-Overway & Guivernau, 2014).

Curriculum We have a wealth of evidence on the difference a quality PE curriculum can make. “…physical education can legitimately aspire to achieve a wide range of educational outcomes for school-age children and youth…” (Kirk, 2013, p. 14). Quality Physical Education guidelines set out by the United Nations Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (2015), aspire to ensure physical education secures a rightful place in school curricula (Kirk, 2010).

Motivation and Confidence (Affective) Current research indicates that development of students’ intrinsic motivation has been associated with: 1) increased intentions to engage in health and skill promoting movement such as exercise (Chen, 2010; Standage, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2003); 2) physical activity during leisure time (Gordon-Larsen, McMurray, & Popkin, 2000; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, Culverhouse, & Biddle, 2003). Physical literacy can be described as a disposition characterized by the motivation to capitalize on innate movement potential to make a significant contribution to the quality of life (Whitehead, 2010)

Movement Competence (Psychomotor) Children’s perceived motor competence has positive implications for their motivation and participation in physical activity (De Meester et al, 2016), and the meaningfulness derived from their experiences (Erhorn, 2014, Gray et al, 2008). Motor skill acquisition and refinement, along with perceived motor competence, that reflect the motivation and confidence to move, (Goodway et al., 2013), is a fundamental part of the framework. Fundamental motor (movement) skills form the foundation of movement competence, and with it, the potential for a lifetime of physical activity (Lubans et al, 2010; Hulteen et al, 2017).

Knowledge and Understanding (Cognitive) When students can regulate or use metacognition (apply knowledge and skillfulness) to their learning, they eventually become their own teachers (Hattie, 2009). Knowledge is a critical component of: 1) skilled motor performance (Bouffard, Watkinson, & Thompson, 1996; Wall, 2004; Wall, Reid, & Harvey, 2007, Tremblay & Lloyd 2010, Dudley, 2015); 2) physical activity participation (Aldinger et al., 2008; Harvey et al., 2009; Tse, 2009) and; 3) physical fitness (Young, Haskell, Taylor, & Fortmann, 1996, Tremblay and Lloyd 2010). An example of embedded cognition is the Teaching Games for Understanding Model (Bunker & Thorpe, 1982).

Consistently Engaged (Behavioural) Physical Literacy requires a holistic engagement that encompasses physical capacities embedded in perception, experience, memory, anticipation and decision making (Whitehead 2001). Understanding children’s engagement in physical activity and aggregated motivation and confidence, knowledge and understanding, and physical competence for physical activity would enable us to better support the development of childhood physical literacy (Longmuir et al., 2015; Tremblay, Collier and Lloyd, 2010).

Student Centred It’s all about the kids! That’s why we’re here. UNESCO’s (2015) guidelines for quality physical education note that “[t]he outcome of QPE [Quality Physical Education] is a physically literate young person, who has the skills, confidence, and understanding to continue participation in physical activity throughout their life-course” (p. 20).

“We believe that students’ physical literacy can grow and flourish as a result of carefully designed experiences in physical education. However, such programming, pedagogy, and practice does not

just happen. It needs to be intentional, guided, and informed by evidence” (Gleddie & Morgan, 2020, p. 17).

To quote our own paper:

“Physical Literacy Praxis bridges theory and practice to provide an evidence-informed framework that educators can rely on to deliver experiences rich in the tenets of physical literacy. The framework has been developed over four years based on an extensive review of the literature, practical discussions with educators, and a small pilot study (paper in progress) at the secondary level—all of which informed the current iteration of the framework. Our hope is that both educators and researchers take up the PLP in their work. We encourage teachers to use the PLP as a guide to inform their practice and enhance the experiences

of their students. We likewise encourage academics to study the framework and add to the body of evidence” (Gleddie & Morgan, 2020, p.17).

Let us know what you think!